History of St Laurence’s Church, Chorley.

Click a button to skip to a section

1793 and all that

What was it all for? Why did our predecessors 200 years ago go to all the trouble (and no doubt expense) of obtaining an Act of Parliament to alter a situation that had existed for centuries? Why did they think it important? How did they go about it? And what was the result?

The notes that follow are an inadequate attempt to answer such questions. Clearly, it is not possible in a short article to explore the many fascinating aspects of our parish’s life at that period. I have, therefore, had to use what historians call ‘broad brush strokes’ and generalisations. Some of the material I managed to unearth at Lambeth Palace before coming to Chorley and may not have appeared in print before.

Nobody can write on any aspect of Chorley’s history without acknowledging a debt to George Birtill. I am very grateful to George for his encouragement to me to write on the history of the Parish Church and for the materials, he has passed on to me. I follow in a noble tradition!

The problem and the challenge

The historical situation

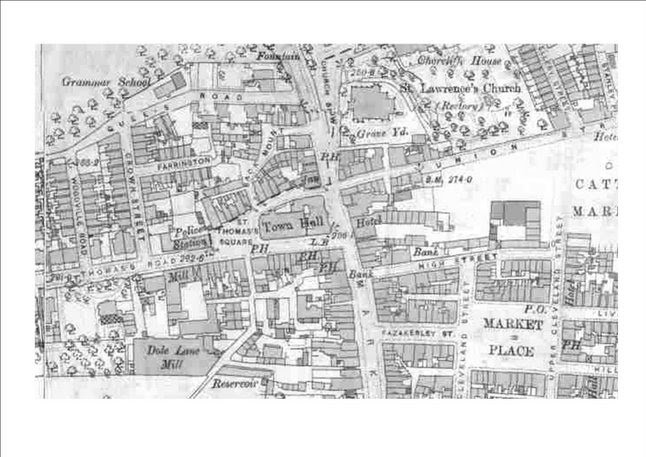

A glance at the map of local parishes in about the year 1600 illustrates the problem immediately. Chorley is the little ‘island’ joined by a ‘tag’ to the Parish of Croston. Croston Parish at that time included a number of townships, some with their own chapels. All the others, however, were geographically part of the same unit. Chorley was not. It was physically cut off from Croston by the ancient parishes of Leyland, Eccleston, and Standish.

Nobody seems to know for certain why this was. (I asked one life-long member of the congregation who said, “Perhaps we were so awkward even in those days, that nobody wanted us!”) It could well have had something to do with the arrangements of the ancient Leyland Hundred. We were not, of course, a unique case. Quite a lot of other parishes in Lancashire had detached bits of territory belonging to them. Chorley formed a clearly defined geographical unit, bordered chiefly by the Yarrow and Euxton Brook.

The arrangement did not always make for good pastoral care. In the days when incumbents did not always reside in their parishes and left even their main Church in the care of a poorly paid Curate, a mere Chapel of Ease was very likely to be neglected. Chorley does not seem to have suffered too badly in this respect. There is a continuous succession of Perpetual Curates from the 16th century.

An unsuccessful initiative

The Churchmen of the Commonwealth period (1645-1660) were concerned to raise the standard of preaching and godliness throughout the nation. One of the ways of doing this was obviously to ensure that each community had its own minister with a clear responsibility for leading its people on in holiness. A survey of parishes was therefore made in 1650 which included Chorley. The survey recommended that Chorley became a parish in its own right, separate from Croston. Church matters moved slowly even in those days, and it was not until 1658 that the Trustees appointed under the Commonwealth gave notice of a meeting to be held to consider the creation of a new parish. The process seems to have been brought to a halt by the collapse of the Commonwealth and the Restoration of Charles II. Quite naturally, there was a widespread desire to keep things as they had been before the Civil War. The raising of Chorley to independent parish status, though a good idea in itself, was abandoned in the mood of the times. By the time of the 1705 national survey of parishes, Chorley was still a chapelry of Croston, with a Curate paid £20 per year by the Rector of Croston. (The Rector’s own income, of course, was derived from the Tithes of the parish. Every parishioner was obliged to give one-tenth of their produce to the Church. That for Chorley would have been stored in the old Tithe Barn, before being used directly or converted into cash. The yearly collection of Tithes was, literally, an annual Stewardship Campaign!)

A new situation

During the 18th century, the rate of change in society began to accelerate. The two Jacobite uprisings of 1715 and 1745 had quite an impact locally, but once they were over, peace brought increasing prosperity and a rise in population. All this, of course, went hand in hand with the Industrial Revolution. Here in Lancashire, our climate produced ideal conditions for the spinning and weaving of cotton. It was as early as 1760 that cotton manufacture reached Chorley. It grew so rapidly that we were one of the towns singled out for a visit by riotous mobs in 1779, seeking to destroy the spinning machines which they thought were depriving the poor of work. A further major development was the enclosure of the ancient common lands around the town in 1767-8. This would have radically affected the nature of the community. No longer were all the townspeople – rich and poor alike – bound together by common ownership and responsibility for the land around the town. Now it was parceled up into individual holdings, with the wealthier members getting the largest share. With most of the land now privately owned, there were no restraints on its sale or use for the new industries. Coal, stone, and iron were also mined and developed in the town.

The result, of course, was a rapid rise in the population and the number of houses in the Chapelry of Chorley. Chorley was probably growing faster than Croston and the daughter was set to overtake the mother!

The situation was clearly becoming unsatisfactory. The pastoral load was becoming very heavy, yet the status and income of the priest actually working among the people of Chorley was no different to that of his predecessors. In addition, the evidence suggests that relations between the Perpetual Curate of the day, Oliver Cooper, and his Rector, Robert Master, were not always of the most harmonious kind. Pastoral efficiency and the carrying forward of the mission of the Church in the new situation made a change in the status of Chorley Chapel urgent. (No doubt too, the local Chorley gentry, who were growing in wealth as a result of the expansion of the town, wished to see their local place of worship (which they were paying to maintain) afforded a suitable status!)

Parliament discusses Chorley

The Journal of the House of Commons records that on 13 February 1793, ‘A petition of the Reverend Robert Master, Doctor in Divinity, Rector of the Parish and Parish Church of Croston, in the County Palatine of Lancaster, was presented to the House and read’.

The petition stated that the Parish of Croston was very spacious and contained many Townships and Chapelries. Some of these, including ‘the Village of Chorley’ are named and described as ‘distinguished and bound by ancient and known Limits and Boundaries’. The Petition admits that the Revenues and Endowments are sufficient to maintain Ministers at Chorley and Rufford, as well as what would remain of the Parish of Croston. It goes on to say that, ‘it would be of great Convenience to the Petitioner, and to the Inhabitants of the said Chapelries if the said Chapels of Chorley and Rufford were separated from the said Parish of Croston and declared to be two distinct Parish Churches’.

The House of Commons clearly listened sympathetically to Dr. Master’s Petition for it gave leave for the bringing in of a Bill to bring about the desired separation and entrusted its preparation to the two local MPs, John Blackburne and Thomas Stanley.

Blackburne (who lived at Hale Hall near Liverpool and Orford Hall near Wallington) and Stanley (a scion of the Earl of Derby’s family) must have got to work quickly for on 1st March John Blackburne presented the Bill to the House of Commons. It was received and given its First Reading. The House resolved that it be read a second time. This happened on 5th March when the Bill formed the first item of business after the House assembled for prayers that day. The Commons resolved that the Bill be committed to Blackburne and Stanley who were to meet that afternoon at 5 o’clock in the Speaker’s Chamber. The purpose of this meeting seems to have been to appoint a Committee to examine the Bill in detail, for the next appearance of the matter in the Journal of the House is on 15 March:

‘Mr. Blackburne reported from the Committee, to whom the Bill for separating the Chapels of Chorley and Rufford from the Parish of Croston. as committed’.

The Committee ‘had examined the Allegations of the Bill, and found the same to be true, and that the parties concerned had given their consent to the Bill, to the satisfaction of the Committee; and that the Committee had gone through the Bill and made several Amendments thereunto’.

After reading the Committee’s report from his place in the Chamber, Mr. Blackburne delivered the Bill with the amendments to the Clerks’ Table.

The amendments were then read through, then a second time, one by one, ‘and, upon the Question severally put thereupon, were agreed to by the House’.

To us nowadays it seems incredible that in the aftermath of the loss of the American colonies and the French Revolution, and with a fast-growing Empire to govern, Parliament should be discussing in detail matters which would nowadays be dealt with by some such body as the Highways Committee of the Borough Council. In fact, at least on the days in question, most of the business of the House of Commons was of this nature. The Chorley Bill was squeezed in among Bills to enclose common lands in Shropshire, build a harbour in Cornwall, create a canal in Berkshire, rebuild Paddington Parish Church, repair the roads in Manchester and so on.

Following its Second Reading and Committee Stage, the Bill finally returned to the House of Commons for its Third Reading on 20th March. In the interval, it had been ‘engrossed’ – printed in a formal style with the amendments incorporated. The House resolved:

‘That the Bill do pass: and that the Title should be, An Act for separating the Chapels of Chorley and Rufford from the Parish of Croston, in the County of Lancaster, and for making them Two distinct Parish Churches’.

The Commons also ordered ‘that Mr. Blackburne

The Journal of the House of Lords suggests that the Bill went straightaway to a Committee, which reported to their Lordships on 25th March. That day seems to have been a particularly busy one for the Bishops: The Bishop of St David’s was handling a Bill to extend the Manchester-Oldham canal; the Bishop of Bangor was concerned with a Bill to enable the Governor and Company of the Bank of England to purchase certain houses adjacent to the Bank; and the Bishop of Gloucester was making sure that the Gloucester Canal Bill got through. In the middle of this flurry of extraordinary Episcopal business, the Bishop of Bangor reported to the House that the Lords’ Committee had considered the Chorley Bill ‘and examined the Allegations thereof, which were found to be true; and that the Committee had gone through the Bill, and directed him to report the same to the House, without any amendment’.

Perhaps none of their Lordships had heard of Chorley, for there does not seem to have been any further debate on the Bill and two days later the House of Lords sent a message to the Commons that they had agreed to the Bill, without any amendment. It received the Royal Assent the following day. The whole process had taken about six weeks (which is a considerably shorter period of time than either the General Synod or the Borough Council would take today!)

An edited version of the Act (with the sections relating to Rufford cut out) was read out in Church at the first of our Bicentenary Services when the Rector of Croston visited us.

What happened next?

It is difficult to know what impact the new status made locally. Robert Master continued as Rector until 1798. It is doubtful whether Chorley ever saw much of him. Oliver Cooper remained as Curate. He died in 1825 and is buried in the Churchyard. There is a memorial to him inside the Church, but his tombstone has been badly damaged and deserves to be restored. Some of Cooper’s descendants still live in the area.

The Master family owned the right to present Rectors to the new Parish and a succession of them served in that capacity until 1880, after which Rectors have been appointed by the Bishop.

It is perhaps a little sad that the Parish Church enjoyed only a brief period as the only Church of England place of worship in the town, following its elevation to independent status.

However, the town was expanding fast and an urgent mission situation presented itself. Thousands of people in Chorley were in danger of going unreached by the Good News of what Jesus had done for them. Our predecessors responded with imagination and faith. They tackled the challenge on two main fronts.

Firstly, they engaged in what nowadays would be called Church-planting. In other words, they created new worship centres in the town, where people could gather to worship, the Gospel could be preached, and from which people’s needs could be ministered to. Over the course of time, these new worship centres became ‘mission churches’ and then eventually independent parishes. St George’s was consecrated in 1826, St Peter’s in 1851, and St James’ in 1878. (All Saints, as a mission from St George’s, became independent in the 1950s.) In this way, many people in Chorley could be given the chance to know Christ and grow as his disciples.

Secondly, our predecessors at the Parish Church adapted their own building to meet the need of the day. In 1859-61 the Church was gutted, the galleries removed, and the north and south aisles added. Not everyone found the changes easy to come to terms with at first. In June 1859 the Rector, Canon Master, wrote that the relocation of the pulpit ‘would give great dissatisfaction to the leading members of my congregation’ and would ‘be attended with great difficulty and meet with great opposition.’ Happily, godly common sense must have prevailed, for the pulpit was moved and the re-ordering of the building went ahead. About twenty years later Rector Edward James (in whose memory the brass eagle lectern was given) abolished the scandal of pew rents, thus enabling rich and poor alike to hear the Word of God and receive the Sacraments. The rest, as they say, is history!

The challenge to us

Nowadays, we tend to think of the past as unchanging. But things did change, often very rapidly. Our predecessors were exactly like us: some welcomed change, others found it harder to get used to. The important thing is that, at the end of the day, they were prepared to make big changes in their worship, their building, and their outreach, in order that in each generation they might fulfill our Lord’s command to make disciples. Here at the Parish Church, we are the heirs of a great heritage. We can thank God with joyful hearts for the faithfulness of those who have gone before us. We must also take up the responsibility for bringing people to a living faith in Christ today. Perhaps, like our Victorian predecessors, we should think about Church planting. Perhaps, again like them, we should be improving the facilities of our building. Certainly, we should be exploring these and other possibilities, just as they did.

To a rather nervous Timothy, St Paul wrote, ‘God has not given us a spirit of timidity, but a spirit of power, of love and of self-discipline; so do not be ashamed to testify about our Lord.’ (2 Timothy 1:7-8). The fact that ‘Parishers’ of old overcame their natural timidity, lived in the power of the Spirit, and told others about the Lord has ensured that there is a living, worshipping congregation in our Church today. Now it is our turn to do the same, so that in a hundred years time there will still be Christians in Chorley Parish Church, praising God for the wonderful things he has done for them in Christ.

Act of Separation

Anno Tricesimo Tertio

Georgii III Regis

An Act for separating the Chapels of Chorley and of Rufford from the Parish of Croston, In the County of Lancaster, and for making them Two distinct Parish Churches.

“Whereas the parish of Croston In the County of Lancaster is very spacious . . . and containeth many Townships, Villages, Hamlets and Chapelries . . . and whereas the Township of Chorley Is itself very populous and the Inhabitants thereof cannot at any time with convenience repair to the said parish Church of Croston, by reason of their remote distance from the same, and of the Inundations of Waters happening in those parts;

“And whereas within the said Township of Chorley there is a Chapel built for the ease of the Inhabitants of the said Township,

“And whereas Robert Master, Doctor in Divinity, is Rector and Vicar and Patron of the said Parish Church of Croston;

“May it therefore please Your Majesty that it be enacted; and be it enacted by the King’s most excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the Authority of the same,

“That the said Township of Chorley. . . shall be from henceforth, for ever hereafter, severed and divided from the said Parish of Croston. . . and that the said Chapel of Chorley shall be for ever hereafter a Parish Church for all the Inhabitants within the bounds or precincts of the said Township, and that the same be named or called The Parish Church of Chorley.

“And that the Plot of Ground now used for a Chapel- yard to the same Chapel shall be and continue for a Church-yard and place of Burial for the said inhabitants of the Township of Chorley aforesaid.

“And that the Inhabitants of the said Parish of Chorley shall be for ever hereafter Parishioners of the said Parish of Chorley, and be discharged and exempted of and from all Repairs and Resort unto the said Parish Church of Croston, And of and from the Cure of Souls, Power and Authority of the Parson and Vicar of the said Church of Croston.

“And that the said Rector of Croston and his successors shall be henceforth discharged of and from the annual payment of Twenty Pounds, which the Rector of Croston hath heretofore usually paid to the Curate of the said Chapel of Chorley, and also be from henceforth discharged from and of the Cure of Souls of the said Parish of Chorley, Provided always that the inhabitants of the said Township of Chorley shall continue liable and pay to the Churchwardens of Croston the annual sum of Seven Shillings which the Inhabitants of the said Township of Chorley have constantly and immemorially paid to the Churchwardens of the said Parish of Croston.

“And be it enacted by the Authority aforesaid that the Parish of Chorley, so separated from the Parish of Croston, shall be deemed and taken to be a distinct Benefice and Rectory within the Diocese and Jurisdiction of the Bishop of Chester for the time being.

“And also be it enacted that the Parson of Chorley and his Successors shall for ever hereafter, by force and virtue of this Act, have, hold, receive, perceive, take and enjoy all such Houses, Lands, Tenements, Tithes, Rents, Oblations and other Parochial Rights, Profits and Privileges whatsoever, within the Precincts of the said Parish of Chorley, which the Rector of Croston might have taken and enjoyed had this Act never been made.

“And It shall and may be lawful to and for any Person or Persons, at any Time hereafter, to give, grant, demise or convey to the Parson of the said Parish of Chorley, Twenty acres of land, or any lesser Quantity, to be Glebe. . whereupon a Parsonage House shall be erected for the same Parson and his successors.”

1890 Discoveries

In October 1890 it was discovered that the flooring in the Chancel beneath the communion table was sinking at one end. On closer examination it was found that two of the three stout beams of oak above the Standish burial-vault had rotted away just where they entered the east wall – the baneful effect of water percolating through the masonry there. Yet such was the strength of the oak beams that they still upheld the double flags above. The present owners of that portion of the Chancel, the representatives of the Carr-Standish family, consented that the vault should be opened, the beams removed, and iron girders substituted in their place, a few feet apart.

St Laurence

Saint Lawrence died August 10, 258, Rome

The prefect of Rome demanded that Lawrence turn over the riches of the Church. Lawrence asked for three days to gather together the wealth and worked swiftly to distribute as much Church property to the poor as possible, so as to prevent its being seized by the prefect. On the third day, at the head of a small delegation, he presented himself to the prefect, and when ordered to give up the treasures of the Church, he presented the poor, the crippled, the blind and the suffering, and said that these were the true treasures of the Church. One account records him declaring to the prefect, “The Church is truly rich, far richer than your emperor.” This act of defiance led directly to his martyrdom. It is said that Lawrence was burned or “grilled” to death.

Myles Standish

Did one of the Pilgrim Fathers live here?

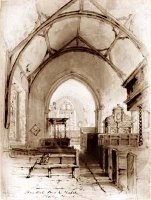

Of particular interest to American visitors is the Standish Pew. This Elizabethan pew was that of the Standish family. Myles Standish, one of the original Pilgrim Fathers will have sat in this pew as a youngster while living at the family estate of Duxbury here in Chorley.

NB Speculation in a book called “Manx Worthies” written in 1901 claiming that Myles was a resident of the Isle of Man has been undermined by recent research.

Carved into the pew, as in other parts of the Church is the coat of arms containing the stars and stripes which it is thought Myles used in New England and which formed the basis for the stars and stripes which now grace the flag of the USA.

The title of this drawing, by WH Bartlett, “Standish Pew & Chapel in Chorley Church”, is in script upper and lower case letters, located below the image slightly to

Recently restored, the monument was begun in 1872 as a tribute to Captain Myles Standish, one of the original settlers of Plymouth Colony. Located atop ‘Captain’s Hill’ – so named because this hill marked the high point of Standish’s 100-acre farm – the 116-foot monument was built of granite from Holowell, Maine. The 14-foot statue of Myles Standish was the work of a Boston sculptor, whose plaster cast was cut out of Cape Ann Granite by two Italian masons.

Origins & Ancestry of Myles Standish

Myles Standish was among the 102 English settlers who sailed on the Mayflower in 1620. A veteran of Queen Elizabeth’s army, having been hired as their military defender, he was chosen to command the first group of men to go ashore when the ship reached New England in November 1620.

Although Plymouth’s early relations with the local Indians were generally peaceful, Captain Standish was occasionally called upon to defend the colony when it found itself at odds with the native peoples.

Like the other Pilgrims, Myles Standish was primarily a farmer. When the original settlers abandoned communal farming in 1627, each family received 20 acres per family member. Half of the Mayflower passengers, including Myles Standish’s wife, died during the first winter. By 1627 he had remarried; with a wife and three sons, he was entitled to 100 acres. He drew a lot that lay at the south-eastern end of the Nook, a 450-acre peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land. Around 1630, this area separated from Plymouth and became the town of Duxbury.

Manxman or from Duxbury?

The Last

“I give unto my son & heire

This clause (Myles’ will) acted like a map of buried treasure on his American descendants, and for generations, they have pursued the Lancashire claims. In the process, they have pieced together a genealogy of remarkable length and distinction.

Yet their search for Myles himself in it has led only to a page in the baptismal register of Chorley parish church for 1584, which they found had been rendered illegible with pumice-stone just at the place where the registration of Myles’ baptism might conceivably have been. Equally negative have been all their legal efforts to recover lost lands in Lancashire.

Or was he from Duxbury?

His name is a household word in New England, but he is barely known

in Lancashire outside the Chorley (Duxbury) and Wigan (Standish) area, and even less in the rest of Old England. He is commemorated locally only by two unobtrusive memorials in St Wilfrid’s, Standish (a

modern stained-glass figure in a crowd and some framed quotations

in the vestry), and by an American flag over the Standish pew in St Laurence’s, Chorley, donated by U.S. soldiers stationed nearby

© St Laurence's Church, Chorley 2021 | Designed by Steffany | Privacy Policy